- Home

- Holly Nadler

Vineyard Supernatural

Vineyard Supernatural Read online

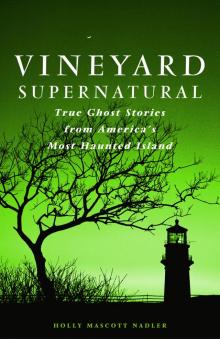

VINEYARD

SUPERNATURAL

VINEYARD

SUPERNATURAL

True Ghost Stories

From America’s

Most Haunted Island

HOLLY MASCOTT NADLER

Photographs by NANCY WHITE

IN MEMORIAM

To my Great Grandma Olga of Lowell, Massachusetts

My father, Larry Mascott

And my departed island friends,

extraordinary people all:

Ed Coogan, Nan Reault, Phil Craig, Tami Pine,

Steve Ellis, John Morelli, and Dawn Greeley

Let’s keep in touch!

Copyright © 2008 by Holly Mascott Nadler. All rights reserved.

ISBN (13-digit): 978-0-89272-755-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

available upon request.

Cover Design by Miroslaw Jurek

Interior Design by Lynda Chilton

Cover photograph © Alison Shaw/Solus Photography/Veer

Printed at Versa Press

5 4 3 2 1

Distributed to the trade by

National Book Network

Author’s Note

I know this from having written two collections of true ghost stories: Even though Americans are more open than ever to the possibilities of a spirit world, other dimensions, and things that go bump in the night besides broken refrigerator belts, it’s still darn hard for people relating their tales to allow the writer to use their real names. One of these fine days we’ll all be able to tell our personal accounts of the paranormal without feeling that at the same time we’re being fitted for straitjackets.

Here’s how I’ve dealt in the following pages with varying levels of skittishness in this regard. For people who’ve been willing to let me use their full names, I’ve used full names. For those who said, “Please keep my identity anonymous,” I’ve stated that their identities have been kept anonymous. For those who hemmed and hawed, I’ve used only their first names. In a few cases, when I’ve decided it would be awkward to call people, say, Girl Number One and Girl Number Two, I’ve given them fictitious first names followed by asterisks.

Finally, over the years I’ve filed away in my noggin stories from people I’m met at parties or street corners or fundraisers for local politicians. These folks are described as I’ve summoned them up from my memory. Who knows what their names were; it was only a little more than a year go that Down East Books and I decided the time was right to produce a second Vineyard ghost book, and only since then have I whipped out a pen and a fifty-nine-cent notebook and said, “Tell me everything!”

I will say this about the details of the upcoming tales: I often have trouble remembering what I had for lunch, but I never forget a good ghost story, whether the experiences were my own or related to me twenty years ago.

1 Why We’re So Haunted

It’s finally happening. In the oldest parts of our country—of which Martha’s Vineyard is one—we’ve stacked up layer upon layer of human history, with all the dramas, clashes, and lost souls imprinted on the air like a tiramisu of sugar, cake, and mascarpone cheese all squashed in a glass bowl.

This island is so richly haunted because it has drawn to its shores many of America’s most restless seekers without providing them with any lasting comfort or solace, beginning with the original band of Puritans who tried to Christianize the resident Indians but ended up killing most of them with European diseases. In the nineteenth century we had a continuous clash between the sacred and the profane as religious groups looked for God and the tourists arriving on their heels looked for saloons and cathouses and cheap real estate. For those with means, the island holds an irresistible beauty, but this ragged, soil-poor land has forced many of the less fortunate inhabitants away to perish at sea (or, in contemporary terms, to be cast adrift in a larger world of asphalt landscapes and death in living).

This is also a place where for centuries secrets have been kept—aided and abetted by reporters and historians—in a manner that jeopardizes the mental health of the living and the psychical health of the dead. When this happens, negative vortices flourish. In these places angels fear to tread, and so do your run-of-the-mill visiting spirits. With the telling of these stories, we can only hope that some of those blockages in our landscape might at last become unstuck.

Good, bad, and indifferent, we’ve got hosts of ghosts. The Vineyard is now on a par with ghost-riddled England, though in both New and Olde England the spirit world has put its own regional stamp on ghostly legends. Instead of chain-clanking dungeons, Martha’s Vineyard has spectral schooners, and instead of castles with ghostly knights and ladies, we entertain the wraiths of Native Americans, runaway slaves, pirates, and mariners, many of them touching down in old captains’ houses or doll-sized Victorian cottages, or hovering in the vicinity of eighteenth-century tombstones that lie forgotten alongside twisting dirt roads.

Vineyarders have always lived just far enough out to sea that in our long lonely winters we may turn a bit mad, hemmed in by frozen shores instead of asylum walls. On the other hand, unlike Nantucket and other more remote islands, Martha’s Vineyard is close enough—seven miles—to the mainland that the tidal currents of the real world keep things stirred up here.

There’s another element in our psychical makeup that I feel compelled to mention: Those of us who live here year-round without trust funds or fortunes made elsewhere are often deeply apprehensive because it’s so very hard to earn a living on this rock where there are never enough jobs. It has always been this way: the summer’s three months of income barely stretching through the desolate months of winter.

And yet we’re loath to leave. The rest of the world seems unnecessarily harsh, unnecessarily … ugly. Here, during an early morning walk you can watch a formation of geese flapping skyward, observe pink mists rising over a saltwater inlet, and pass by a twinkling, frosted field stretching to a stand of snow-capped pine trees. Living here feels like a doomed love affair; it brings you no peace, but you know your lover is more beautiful, more exciting, and infinitely more kind than anyone else in the world. This brand of agony and ecstasy attracts both angels and demons to the Vineyard. It also recalls certain souls who have ostensibly passed on but who find it just as difficult to leave the island in death as in life. Call it a spirit world agoraphobia.

A gentleman from Dublin who visited my bookstore recently said with a small amount of pride, “In Ireland, ghosts’re thick as molasses.”

Here too.

Lately I’ve been advising people to stop ignoring the eerie stimuli bombarding their sixth sense, and to take note of the experiences that let us know we’re not alone here, we easily frightened, fragile, alive ones. A normal person’s day is packed with the supernatural, and yet we unceasingly convince ourselves we only imagined the evidence of it; what just happened couldn’t have happened.

Even those of us who believe we dwell within a prism of universes are habitually blind, deaf, and dumb to most of it: the footsteps in the attic (as we remind ourselves we have no attic, hence no footsteps), the stunning coincidences, the precognition of a phone call or a visit, the lost object that suddenly seems to find us, the tap on the shoulder when no one’s there, the charged atmosphere that repels us as we round the corner of a two-hundred-year-old shipping station, an old farmhouse that gives us the willies—the same one where the owners have moved out, where painters and carpenters have refused to work alone in certain rooms, and where a neighbor has heard screams erupting late at night from the “empty” third floor.

My own haunted life on the Vineyard has its cycles and seasons. Sometimes months go by when nothing happens, but then there are the active pe

riods …. Here’s an account of a typical day during one of those times.

I live over my little bookstore in Oak Bluffs, and I start each morning by leading my Boston terrier, Huxley, through the shop as we head out for our early morning walk. A little plump, square book with a green cover sits on the counter: Everyday Positive Thinking by Louise L. Hay & Friends. Hmm … I know I catalogued this into the system the previous afternoon, finding a spot for it on my Mind/Spirit shelves. I remember it vividly because a volume of such dinky proportions is hard to place with the normal-sized books.

Another oddity: The door to the basement, closed and locked the night before, stands open—again. One of the tiny decorative lamps under the high ceiling is dark, but I don’t bother to drag over the stepladder; the light will fuse on again by itself. (I learned this lesson after months of changing perfectly good, working bulbs.)

It’s a sparkling blue and gold October morning, and Huxley and I head through the Campground, a village of three hundred exquisitely preserved Queen Anne cottages. Most of the owners have left for the season. Pastel shutters are closed and tightly fastened. The gingerbread-style porches have been cleared of their wicker furniture. I hear the lonely tinkling of a set of overlooked wind-chimes. I can feel the brooding regard of nineteenth-century grandmothers, restored to younger versions of themselves—and restored, now and then, to this place. But this impression of mine is personal, subjectively perceptual, and even though I’ve glimpsed two ghosts here—one a Confederate soldier, the other a more modern figure in a silvery grey tee-shirt—I rarely volunteer this information unless I’m certain of an open-minded reception. We so-called sensitives (I think of it more accurately as susceptibles) have learned how to at least appear sane.

Later I tell my friend, petite, brunette art dealer Paula, about my pipe dream of selling the bookstore and spending at least six months each year in a monastery in Italy. “I feel Assisi calling to me,” I say.

She glances over my shoulder and exclaims, “Wow! Two monks were just staring in your window!”

Monks? In true monkish robes? In America? Nowadays Catholic clergy wear sneakers and Red Sox tee-shirts, do they not? I pad outside to see for myself. Sure enough, heading up the street are two friars clad in plain brown cassocks with hoods, a monastic couture made famous by the thirteenth-century saint, Francis of Assisi.

In the evening of this typical day when the force is with me, Huxley and I stroll down to the harbor. Only a couple of sleek sailboats rest at anchor this late in the year; the other vessels are all hard-working fishermen’s trawlers. As Hux and I wander along the seawall, then head home through the meandering lanes of the Campground, at least one of the tall town lamps winks off as we pass underneath. When this first started happening, a couple of weeks before, I’d paid little attention. Then I realized that this nightly plunge into darkness had been occurring way too often, with me and my dog always perfectly centered beneath the halogen globe as it went dark. The problem has to be more than a mechanical glitch. This was a poltergeist greeting of “We’re here, babe!” on this haunted isle.

A serious theme is growing within the carnival atmosphere of ghost magazines, paranormal societies, and Web sites where people share their photographs of mysterious glowing orbs of disembodied energy. Fifteen or twenty years ago, few Americans had ever heard of guided walking tours past haunted houses, but now we find these walks everywhere, from Key West all the way up through the Civil War battle sites, Savannah, Charlestown, Cape Cod and the Islands, Boston, and most dramatically, Salem, Massachusetts, whose last Halloween Week attracted so many visitors that traffic came to a standstill on Interstate 95 a few miles to the west.

Ghost stories have always been fun. Let’s not disparage or cease to enjoy their entertainment value. But writers and researchers into the paranormal such as Paul F. Eno (God, Ghosts, and Human Destiny), the Vineyard’s own Reverend S. Ralph Harlow (Life After Death), and, more than a hundred years ago, the brilliant psychologist and philosopher and cofounder of the American Society for Psychical Research, William James (Varieties of Religious Experience) have found within the nether world of spirits a vital tool for their own personal theology.

And how could it not become personal? A strict adherence to a single faith is almost unheard of today in the ranks of the educated, introspective, seeking segment of the population. Rarely do you meet an agnostic raised as an Episcopalian who hasn’t delved into Buddhist meditation, a reform rabbi who isn’t conversant about Julian of Norwich or Jalaluddin Rumi, or anyone at a fundraiser who hasn’t attended at least one Hindu darshan, or had a tarot reading, a reiki treatment, or a good soak in a Lakota sweat lodge. Recently I saw a bumper sticker that proclaimed: GOD IS TOO BIG TO BE STUFFED INTO A SINGLE RELIGION. (Caveat emptor: Anyone who doesn’t agree with this philosophy probably shouldn’t be reading this book.)

And how does a credible ghost story or direct experience of the supernatural play into some sort of connection with the Divine? Well, first, in our search for a vital Reality, we long to know that there’s more to life than what our five senses reveal to us. When a deceased relative causes her favorite rose bush to bloom in January, or a transparent woman in a Victorian nightgown appears at the end of our bed, we become aware that other dimensions exist, that if there’s a world beyond death, there may also be multiple universes snapping, crackling, and popping within us and without us—and all of it connected, right down to the smallest particle of the atom as well as to the farthest electron spinning at the outer rim of time and space.

If you start with a ghost and end up pondering quantum psychics, you realize it all comes together with a big red bow and a gift card signed God or Spirit or Ground of All Being or (fill in your own blank).

Scratch the surface of anyone fascinated by ghosts and you’ll find a natural-born theologian.

2 How We Collaborate With Ghosts

Theology aside, we must not lose sight of the entertainment value of a good story of the supernatural.

Who’s having a better time around a campfire when a tale is being told about Bigfoot? Is it the listener who shudders and steals a glance into the pitch black woods, then, stifling a giggle, grabs the arm of her companion? Or is it the guy seated on the far side of the orange embers who rolls his eyes and sneers, “You suckers are falling for this?!” Not only is this uncharming cynic having no fun, but everyone around him is having less fun because he’s there.

I learned this lesson—about the pure glee that accompanies an open mind—on a seventh-grade debating team when the hot-button topic was whether UFOs really exist. I volunteered for the No side, thinking this would be a shoo-in to win the debate, since all smart people are science oriented, and science has never (supposedly) come up with a single shred of evidence for UFOs.

Boy, was I wrong. About the shoo-in part.

As we members of the smart, scientific No team rattled off data about how prohibitively long it would take for intelligent life from another galaxy to shuttle here, and why would extraterrestrials be interested in our little planet anyway, tucked as it is in the Podunk of the Milky Way, the other side of the debate—the Yes kids—rolled out one juicy UFO saga after the next.

Suddenly I wished with all my heart I’d volunteered for the Yes team. I would have loved to be the one relating an eyewitness account of a farmer outside Wichita who, one evening while driving his tractor, was suddenly blinded by a flurry of incoming lights, after which his three-ton vehicle, with him still in the driver’s seat, levitated fifty feet off the ground, hovered over his grain silo, spun right, then left, then exploded in a red fireball, after which, two hours later, the farmer woke up in the middle of his own frozen asparagus field. He was able to prove this whole episode truly happened by holding up his hand with the tractor’s steering wheel—all that remained of the beleaguered vehicle—heat-soldered to his palm.

Ludicrous? Of course! I would only believe this story if I had been seated beside the farmer on the tractor-turned-helicopte

r. But it could have happened, right? That half-second pause to consider the possibility, however slim, lends an extra delight to the tale—to all tales. (In fact, we’re disappointed when the supernatural element is removed. Consider John Travolta’s paranormally induced hyper-genius in the movie Phenomenon turning out to be a simple brain tumor; didn’t that take all the starch out of the story?)

So, by all means, let us exercise good judgment, but at the same time let us leave ourselves open to the possibility that something truly weird and wonderful could happen to any one of us. Being smart and open-minded and possessed of a sense of humor will enable us to change the world.

Finally, we alive ones work in collaboration with all the dead souls, angelic forces, and negative entities with whom we share a common space. This movie we’re filming together has a longer credit roll than any mere Hollywood production.

Here’s a sample scenario, assembled from several true stories:

A brand-new six-thousand-square-foot trophy house sits on a cliff overlooking the Atlantic Ocean on the southwest-ernmost part of the island. Five hundred years ago, a tribe of Pokonockets pitched their tents here in the summer. They fished from the beach below and gathered wild grapes, beach plums, and bayberries in the surrounding fields. As the years went by, the tribe slowly moved its tents farther west and the original site became their burial ground.

In the mid-1600s when the first European settlers started making tracks on the island, a single white male with a high threshold for privacy bought this acreage and built a rustic homestead only a notch above the meanest shack. He married a young Pokonocket woman with whom he sired a family of thirteen children, nine of whom survived into adulthood. The man and his family were absorbed into the native community.

Vineyard Supernatural

Vineyard Supernatural